This post will look at how psychological distress may play out among queer and transgender people and give you an introduction to the concepts of trauma, PTSD and Complex PTSD (CPTSD) in an LGBTQ+ setting. I will point to some steps you could take to help yourself or a friend suffering from trauma related issues.

By Sally Molay

If the headline above caught your attention, you might know someone who struggles with the effects of trauma. Or maybe you suspect that you yourself carry unresolved trauma and the time is right to look into that. In either case, welcome to this primer and good luck in your important work!

Please note: I am not a doctor or a psychologist. This is not medical advice. I am a queer person and a trans ally. I suffer from complex trauma from childhood emotional abuse. I am also a survivor of sexual assault. I have been fortunate enough to heal and learn through years of therapy. I am also a trained instructor of iRest, a research-based relaxation and meditation technique for healing trauma.

I would like to underline that being trans is not a mental illness. Having a sexual orientation different from the straight one is not a psychological disorder. The current medical manuals explicitly state that being trans is not a mental illness. However, the ways a cis/hetero-normative world treat queer people can often cause trauma. Moreover, queer and trans people are people like other people, and as such they can face emotional challenges that are not directly linked to their gender identity or sexual orientation.

Which topics are covered?

This is a lengthy post. If this feels daunting, I have included this little menu that you can use to jump to the parts you want to investigate:

- What to do if you are in distress right now

- Why write about trauma in an LGBTQ+ context?

- What is a trauma?

- Flight, fight, freeze, fawn

- PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder)

- Complex PTSD

- Somatization (bodily expressions of trauma)

- The window of tolerance

- How to get help

- How to help yourself

- Resources

What is trauma?

Trauma is an emotional response to something terrible. Trauma and their effects are natural phenomena. You are not mad. Your mind and your body are simply trying to cope as best as they can.

Trauma can lie buried for long periods and then surface unexpectedly. This can be an overwhelming experience. If you are traumatized and recovering, a trauma response can be triggered by different circumstances.

Being triggered can make you panic, feel overwhelmed, cry, act out, withdraw, or react defensively. First and foremost, know that this is a normal reaction to extraordinary circumstances. There is nothing wrong with you as a person. But you are in a difficult situation.

What to do if you are in distress right now

|

| Instagram-photo made by the artist Michael James Schneider. He has published a series of mural texts like this one. |

Maybe you found this post because you are in distress right now. In that case, here are some steps you can take immediately to feel better:

If you are not safe right now, try to remove yourself from the threatening situation. This might not always be possible. But if you can, go to a friend or relative that supports you. You don´t have to explain what´s going on. Simply say that you want or need some friendly company. If this is not an option, go to a café, a mall, or a cinema – somewhere with crowds of people, where you can sit down and relax for a bit.

If something illegal is going on, you could go to the police. Unfortunately, in many parts of the world, LGBTQ+ rights are not protected by law or the police might not be known to be helpful to minorities. In this case, LGBTQ+ organisations might have a shelter or a crisis team.

If you are safe, you might want to connect with a friend or reach out to a help line or an online support forum. Later on, you might look into finding an open-minded pro-LGBTQ therapist or counsellor.

Why write about trauma in an LGBTQ+ context?

Being an LGBTQ+ person is not a mental health diagnosis. If you struggle with your mental health, that is because of other circumstances, such as bigotry and discrimination.

Not all LGBTQ+ people carry trauma, but many do. Living in the closet, family rejection, bullying and violence are some of the reasons for this. The general lesbophobia, homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia in society can be sufficient in many cases.

LGBTQ+ people unfortunately experience bullying, harassment and even violence more often than most people. In addition, many of us do not have safe ways to explore our sexuality or gender identity. This makes us vulnerable to sexual trauma. LGBTQ+ people are also more likely to be homeless than others. Being unhoused can be a trauma in itself. And it makes people especially vulnerable to violence.

Because they cannot safely be themselves, LGBTQ+ people sometimes repress their entire identity. This can go on for years or even decades. The pressure of hiding your true self and the fear of being found out can be traumatising. When the repressed identity surfaces, this can be a relief, but it can also be a forceful, dramatic, painful and scary experience.

Many LGBTQ+ people who suffer the effects of trauma are unaware of this. We often disregard or distrust our own experiences. This comes from being surrounded by straight friends and family as well as heteronormative, cisnormative media or even laws. We are told in a myriad of ways that what our heart tells us is wrong. It is difficult not to internalize these prejudices and feel shame for what makes us unique. We might feel that our feelings and our trauma are not “real” or valid.

Finding constructive ways to deal with trauma is the next challenge. This is demanding for anyone, and it can be especially demanding for LGBTQ+ people. Our trauma might not be safe to talk about. It is challenging to find a therapist who understands our predicament.

There are no easy fixes for this. But a good place to start is to learn about trauma, PTSD and CPTSD, the symptoms you might experience, your triggers and some ways to meet them. Knowledge is a valuable resource in any recovery process. In marginalized communities it is even more valuable.

|

| Some trans and queer people repress their identity in order to please their family, friends and peers. Photo: recep-bg |

Defining trauma

“If you are experiencing strange symptoms that no one else seems to be able to explain, they could be arising from a traumatic reaction to a past event that you may not even remember. You are not alone. You are not crazy. There is a rational explanation for what is happening to you. You have not been irreversibly damaged, and it is possible to diminish or even eliminate your symptoms.”

Peter Levine in Waking the Tiger, Healing Trauma

According to Dr. Nicole Le Pera, trauma cannot be precisely defined because it is a subjective experience: “Trauma refers to any event that overwhelms our capacity to cope, leaves us helpless to escape or say no, and leaves us in isolation (alone) to deal with the consequences of these events.”

It is a common misunderstanding that a trauma must be a single experience, like a car accident. There are also complex traumas: When you are not protected or cared for as a child or young person, or are hurt or betrayed, this can cause trauma. You might not recognize the effects until much later. You most likely force yourself through the obstacles you are facing and keep going. When you are safe, or at least safer, the effects of the trauma can catch up with you. This can happen slowly or suddenly.

Not everyone who experiences such threatening situations are traumatised. Highly sensitive people are more likely to be traumatized than others. This also depends on several factors such as your previous experiences and your support network.

LGBTQ+ people sometimes have lives where one crisis is piled atop the other. We might not have anyone to reach out to when we need help. Our crises might be related to something that is considered shameful or taboo in our society and needs to be kept secret. These are all factors that can contribute to turning a crisis into a trauma. It also means that LGBTQ+ people are more likely to experience complex trauma.

If you suffer from the effects of trauma, remember: Your trauma is valid. Whether it is new or old, secret or shared, big or small, your trauma is real, and you deserve help and recovery.

Flight, fight, freeze, fawn

To understand trauma, we must also understand our survival mechanisms. It is helpful to know how they come into play, both during the traumatic experience and later. That which helps us survive in a crisis, can make problems for us in the aftermath.

New-born babies cry out to their caregivers for care, safety and soothing. At any age, calling out for help is often the first reaction when we are in danger. If we do not receive help to get safe, the next line of defence is the fight or flight system.

Flight

Flight is often the first impulse when we are in danger and without help. The body releases the stress hormones cortisol and adrenalin, which activates our bodies, so we are ready to “put the pedal to the metal” and flee. Our heart races, blood is redirected to the muscles so we can act quickly, and we search for a way out.

Unfortunately, there are situations where flight is not an option, like when a person is trapped or immobilized or simply has nowhere to go. This is the case if the threatening person is also the caregiver. If flight is not an option, the next impulse is to fight your way to safety.

Fight

The fight impulse mobilizes the body in the same way as the flight impulse. But now the focus is to fight the threat so we can be safe. If we lack the physical or systemic power to vanquish the threat, the passive defence is activated.

Freeze

When we freeze, our body is still highly activated. Our nervous system still has the “pedal to the metal”. Simultaneously, the “breaks” are activated. We become rigid and immovable, like a deer caught in the headlights. The deer remains frozen until the car has passed. When we find ourselves frozen in a situation that doesn’t pass, the body’s passive defence is activated: We become limp and pliable in order to survive.

Fawn

In the fawn state, the activation is toned down and the “breaks” are in charge. Blood leaves our muscles so our body becomes limp. Hormones are released to make us numb. This is what happens when a threatened animal plays dead.

Using words like “play dead” makes it sound like this reaction is a choice. It is not. Many people are ashamed that they did not put up a fight. So please remember that this is all about instincts and biological reactions.

A passive defence is the best in many cases. Like when we have to endure pain over a long time or find ourselves with no way to escape. The passive defence will ease the pain and suppress reactions that could be dangerous. For instance, it can tone down our aggression towards an assailant.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

When trauma leads to a disorder, some, or all of the four defences (flight, fight, freeze, fawn) continue to influence our behaviour long after the traumatic incident is over. This is PTSD or CPTSD. You might find it annoying or shameful because these biological reactions feel beyond your control. Please remember that when we understand our reactions better, we can have more control over them and chose our reactions more freely.

According to the Mayo Clinic, post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD is a mental health condition that is triggered by a terrifying event or events — either experiencing it or witnessing it.

Most people who go through traumatic events may have temporary difficulty adjusting and coping, but with time and self-care, they usually get better. If the symptoms get worse, last for months or even years, and interfere with your day-to-day functioning, you may have PTSD.

Symptoms of PTSD

Symptoms may start within one month of a traumatic event, but sometimes they do not appear until years after the event. PTSD symptoms vary over time and from person to person. They are generally grouped into four types:

- Intrusive memories

- Avoidance

- Negative changes in thinking and mood

- Changes in physical and emotional reactions

Intrusive memories, or flashbacks, is what happens when a soldier relives the horror of war after hearing a loud bang. More often it is unwanted, distressing memories or upsetting nightmares about the traumatic event. It could also be emotional distress or even physical reactions to something that reminds you of the traumatic event.

Avoidance means trying to avoid thinking or talking about the traumatic event. Or you could find yourself avoiding places, activities or people that remind you of it.

Negative changes in thinking and mood might feel similar to depression. But you might not feel bad. Instead, you might feel emotionally numb. You could also experience memory problems, including not remembering parts or even all of the traumatic event.

Changes in physical and emotional reactions can mean you are easily startled or frightened. Or you could always be on guard for danger (hypervigilance). You might also have trouble sleeping or concentrating. You could be irritable or aggressive, or even self-destructive, such as drinking too much or driving too fast.

For years, my most noticeable symptoms were anxiety and depression. After some therapy and recovery, I discovered that there were other symptoms “hidden” by the anxiety and depression, like guilt and shame, avoidance, numbness, brain fog and hypervigilance. This is when I realized I had PTSD. I also experience some physical symptoms. When psychological distress causes physical symptoms, this is called a somatization.

Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD)

According to the CPTSD Foundation, Complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) is the result of ongoing, inescapable, relational trauma. Unlike PTSD, Complex PTSD always involves being hurt by another person (or persons). These violations are ongoing, repeated, and often involving a betrayal and loss of safety.

Unfortunately, many LGBTQ+ people experience the kind of ongoing hurt and unsafety that can cause complex trauma.

The symptoms of CPTSD are similar to symptoms of PTSD, but may also include:

- Feelings of worthlessness, shame, and guilt.

- Problems controlling your emotions.

- Finding it hard to feel connected with other people.

- Relationship problems, like having trouble keeping friends and partners.

- Dissociation is a mental process of disconnecting from one’s thoughts, feelings, memories, or sense of identity. This is a way the mind copes with too much stress. Periods of dissociation can last for a relatively short time (hours or days) or for much longer (weeks or months). The most common form of dissociation is “spacing out” and realizing time has passed without your notice.

- Ongoing dissociation can lead to what is called a depersonalization or derealization disorder, where you persistently or repeatedly have the feeling that you're observing yourself from outside your body. Things around you seem distant or unreal. This is an extreme way for your body and psyche to try to protect you from severe threats, whether they happened in the past or are present here and now.

CPTSD is a newer diagnosis than PTSD, and it took years before I found information about it. When I read descriptions of how it affects your ability to regulate your emotions, and about dissociation, I realized that this applied to me. After years and years of gaslighting and manipulation in my childhood home, I sometimes can’t contain strong emotions. When this happens, I “space out” and lose touch with what goes on around me. This was sad to realize, but also empowering: More knowledge about the problem brings the solution closer.

|

| Trans and queer people who grow up in a hostile environment are often constantly questioning their identities and their right to be loved. Photo: Bulat Silvia |

Somatization

Somatization is pain in the body caused by an inability to express emotional pain in words. According to Alexander C. McFarlane, of all the psychiatric disorders, PTSD most often lead to somatization and particularly medically unexplained pain.

Somatization can happen when your trauma must be hidden. LGBTQ+ people experience this growing up in a family or culture that is hostile. Carrying this distress in secret for years can build a huge emotional pressure. When the pressure mounts, the distress has to be communicated: The mind transforms the internal, mental distress into physical symptoms. This could be headaches, dizziness, muscle aches, fatigue and more.

Remember that these reactions are rooted in biological reactions, the ones we share with many animals. A fight or flight response is physiological as well as mental, and if we cannot shake the stress off afterwards (as dogs do, for instance), your muscular system may remain tense, creating a kind of protective “muscular armour” that is bound to cause pain, fatigue and other physiological problems.

I have had periods of fatigue since my teens. Sometimes I can push through and keep showing up to work. Sometimes I can’t. The fatigue can last for days, weeks and months, and is accompanied with aches in my muscles and joints. Learning about somatization I realized that this does not happen because I am weak, but because of trauma. This knowledge makes it easier for me to cut myself some slack and to give myself what I need to heal.

Destructive coping strategies

The untreated effects of trauma may lead some people into adapting unhealthy coping strategies. These include substance abuse, eating disorders, and self-injury.

Gender dysphoria may, for instance, alienate some trans people from their own bodies, leading to neglect of bodily needs, with various health problems as the end result. This may in turn make anxieties and depressions even harder to bear.

This is why it is so important to become aware of one’s gender variance or sexual orientation. You cannot connect the dots of this complex system of causes and effects before you accept yourself for who you are. When you have reached that point, however, it becomes much easier to find ways of affirming that identity and find friends who accept you for who you are.

The window of tolerance

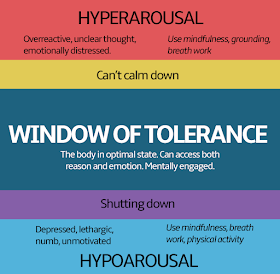

|

| Adapted from an illustration by Richard Bamford Therapy. |

The window of tolerance is a model that describes how our physical activation varies. It illustrates what happens when you feel threatened and can help device a strategy to feel better:

Inside your window of tolerance

When you are inside your window of tolerance, you can interact with people comfortably and readily receive, process, and integrate information. Above or below your window of tolerance, you are in survival mode. You are primed to act, and it is harder to think clearly. When you are not within your window of tolerance it is hard to explore, learn and connect to others.

Above your window of tolerance

Above your window of tolerance (hyperarousal or overactivation), it is “pedal to the metal”. Flight or fight responses are activated. This makes it harder to think clearly. You might also have a hard time regulating your emotions.

Below your window of tolerance

Below your window of tolerance (hypoarousal or underactivation), passive responses are activated. The “breaks” are on. The fawn response is a state of underactivation. In freeze mode you are both overactivated and underactivated, both above and below your window of tolerance.

The size of your window of tolerance

The size of your window of tolerance is determined by how much activation it takes to mobilize the survival mechanisms of flight, fight, freeze, or fawn. This varies based on our experiences, situation, and current condition. Sometimes you can take a lot of stress, sometimes less. With PTSD or CPTSD, the window of tolerance has diminished over time. Your defences are more easily triggered.

Managing your window of tolerance

The more time you spend within your window of tolerance, the wider it gets and the easier it gets to stay there. The figure above, suggests some steps you can take to return to your window of tolerance and stay there even when you are triggered. You will find more tools and strategies below.

How to get help?

If you suspect that you suffer from PTSD or CPTSD, it is advisable to have the diagnosis confirmed by a doctor. If you have access to an LGBTQ+ friendly doctor, they can help with this. A doctor might also refer you to a psychologist. If you have access to a psychologist, that is very helpful.

Even without a doctor or a therapist to help you, there are many ways to get help:

- Talk to a trusted friend when you feel ready.

- Find PTSD support groups online or where you live.

- Be proud! Celebrate your queerness in big or small ways. Find LGBTQ+ community online or where you live.

How to help yourself

It might be hard for you to find help. There are still a lot of ways you can help yourself:

Take whatever steps you can to be safe. Remove yourself from dangerous, threatening, or invalidating people if possible.

|

| Healing is not linear (adapted from this Reddit post). |

Cut yourself some slack. Recovery is hard work and can take time. You are doing your best in a difficult situation.

Know your triggers

Triggers are situations that switch on your defenses. This could be for instance:

- Meeting people who have hurt you

- A “trauma anniversary”, the day or the time of year that you suffered a trauma

- A season – Christmas is particularly triggering for many people who suffer from childhood trauma

- Seemingly innocent input, like a smell, a sound, or a situation that for some reason reminds you of a threatening situation or person. For instance, I am still triggered by my mother´s perfume, 30 years after I moved away from home.

Knowing your triggers gives you options and agency. For instance, you can choose to avoid a triggering situation on an already bad day. Or you can prepare yourself and take steps to feel safe.

Get grounded

When you are triggered, your attention is focused on a crisis in the past or in the future. The best thing to do is to return your attention to the present moment. The 5-4-3-2-1 Coping Technique is research based, tried, and tested.

You could choose an object to remind you that you are safe, a link to the present moment. It could be anything, e.g. a pretty rock, an acorn or a little ball. It should be an object that you enjoy and that fits in your pocket.

You could make your own connector. Choose an object to remind you that you are safe, a link to the present moment. It could be anything, e.g., a pretty rock, an acorn, or a little ball. It should be an object that you enjoy and that fits in your pocket.

Go for a walk. Any walk is good. A park, a beach or a forest is great. You don’t have to make it a long or strenuous walk. All it takes is a little movement, daylight and feeling the ground beneath your feet.

Connect with a friend. The very best option is a real-life meeting and a big hug (if that is your thing). Hugs release a calming hormone, oxytocin. You can get a similar effect with this Hand on Heart technique:

You could tell your friend what troubles you. Sharing your thoughts and feelings can be comforting and calming.

Connecting online is a good option too. You can find online spaces for LGBTQ+ people or groups for trauma recovery.

Breath work

Breath work is a great way to help regulate your emotions. Bear in mind that it can be challenging if you are very triggered. See what works for you.

If you are overactivated, you can lengthen your breaths to calm yourself. Try this:

- Breathe out through your mouth counting to three

- Breathe in through your nose counting to three

- Repeat 4-5 times

- Lengthen your breath by counting to four next, then five

Bee breath is a practice from yoga. It is wonderfully playful and calming:

- Gently close your eyes if that feels comfortable. Keep a gentle smile on your face.

- Place your index fingers on the cartilage between your cheek and ear to close your ears.

- Take a deep breath in, and as you exhale, make a humming sound like a bee.

- Make a high-pitched sound, imitating the buzz of a bee

- Repeat this pattern five to nine times.

Box breathing is developed for Navy Seals and provides stress relief. This is a good choice when you are underactivated:

- Start by releasing all of the air from your chest

- Hold your breath for 4 seconds

- Breathe in through the nose for 4 seconds

- Hold your breath for 4 seconds

- Exhale out of the nose for 4 seconds.

- Repeat as long as comfortable or you feel invigorated

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is the practice of purposely bringing your attention to the present moment experience without evaluation or judgement. It has roots in Buddhist and Christian practices. Modern mindfulness is a secular, research-based practice. Research shows that it is a good way to reduce stress.

One mindfulness technique is to follow your breath. If you are curious about this, you could try this short, guided practice:

Another type of mindfulness is a body scan, where you move your attention systematically around your body. This can be a good way to relax, and it can ease body aches from stress and somatization. Some people do not enjoy this prolonged focus on the body. Give it a try and see what you think:

If you find these mindfulness practices helpful, you can find guided meditations and imagery, body scans, and more on Insight Timer.

Find distraction

If you are overwhelmed, connecting or sharing might be too much to handle. It could stir things up even more. In this case, it is better to find a distraction. What works best is individual. Here are some suggestions:

- Enjoy a fragrant, warm cup of tea

- Listen to your favourite music

- Dance

- Play a game on your phone or computer

- Watch a TV series or movie you love

- Read a book

- Cuddle with a pet

- Go for a walk

- Play a sport

Resources

Communities

Fight through mental health is a Discord server where you can ask questions, get support, and connect to others working on their mental health.

rPTSD is Reddit’s PTSD subreddit. You can use it to share your story, ask questions, find resources for recovery and self-care, and get judgment-free support.

MyPTSD is a forum for peer support for PTSD and CPTSD.

TrevorSpace is an affirming, online community for LGBTQ young people between the ages of 13-24 years old.

QChatSpace is a community where LGBTQ+ teens can chat with peers, find and give support, have fun, connect around shared interests and get good information.

7 Cups LGBTQ Chat Room & Support Online, where you can xhat online with LGBTQ active listeners for support.

LGBT Space is a a place to meet other people and stay in touch with friends, a mixture of social media, friendship app, community platform and a dating site.

British organizations and helplines.

Helplines

Switchboard LGBT+ Helpline, a safe space for anyone to discuss anything, including sexuality, gender identity, sexual health and emotional well-being.

Trans Lifeline is a trans-led organization that connects trans people to the community, support, and resources they need to survive and thrive. Peer support hotline available 24/7 in English and Spanish in US and Canada.

Books

Dawson, Juno: Mind your head, Hot Key Books, 2016. 208 pp.

Huber, Cheri: There is nothing wrong with you: Going Beyond Self-Hate. Keep it Simple Books, 2001. 264 pp.

Van der Kolk, Bessel M.D.: The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, Penguin Publishing Group 2015. 464pp.

Levine, Peter A.: Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma, North Atlantic Books 1997. 288pp.

Miller, Richard Ph. D.: The iRest Program for Healing PTSD: A Proven-Effective Approach to Using Yoga Nidra Meditation and Deep Relaxation Techniques to Overcome Trauma, New Harbinger Publications 2015. 224 pp.

Online articles

Zinnia Jones: Depersonalization in gender dysphoria: widespread and widely unrecognized

Cleveland Clinic: Transgender: Ensuring Mental Health

Mental Health America: LGBTQ+ Communities and Mental Health

Rethink Mental Illness: LGBT plus mental health

7 Ways to Use Your Own Body to Reduce Stress

Top illustration: Lorenzo Donati

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteOlder trans people have a far higher propensity to shoulder unresolved trauma due to having been raised during a more difficult time. There may have been episodes which marked them before they were forced to repress and live in silence until such time as it necessitated addressing because the lid could no longer contain it. Excellent article :)

ReplyDeleteWhat you say makes sense. After all, we shouldered all kinds of external and internal turmoil for decades. That said, it's not all lollipops and roses for today's trans kids and young people.

DeleteI am close friends with the mother of a trans daughter who has been fully supported almost from the moment she announced her authentic gender. Now, she's a delightful and precocious 15 year old living mostly in stealth even here in the Seattle area. I can only imagine how stressful it is for her keeping and maintaining her secret while also maturing and exploring dating. And then... she has to look forward to eventually meeting someone she gets serious with—before and after GCS. Knowing that at some point she must vulnerably share this with dates, and later, knowing that she will not be able to bear children. All these potential deal-breakers ahead of her that she undoubtedly ponders.

Now, we had those too. In my case I was so deeply ashamed of my inner feelings and desires that for decades I didn't even tell my therapist(s) let alone girlfriends and wives (2).

To sum up, I don't think it's beneficial to compare scars. It's better to approach people where they are and try our best to help.

Thank you, Joanna, for your very relevant comment. Yes, older trans people are definitely at higher risk both for having sustained trauma and having had to repress it.

ReplyDeleteWhen repressed trauma resurfaces, it is eventually a good thing, an important step towards recovery. But when the lid comes off, it is very challenging.

Oh believe me Sally I only know too well :)

DeleteI am sorry to hear that, Joanna.

DeleteTook a few years of blogging :)

DeleteSally, thank you. This took quite a while to write and edit, I'm sure. Such a comprehensive and helpful overview of very important topics that would help anyone, LGBTQ+ or not.

ReplyDeletePlease give my best wishes to Jack.

Thank you for your feedback, Emma! Jack sends warm regards.

Delete